National Moth Week

The last week of July marks National Moth Week, a whole week of events focused entirely on moths.

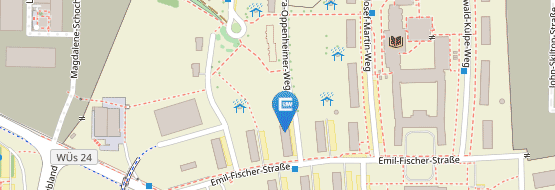

To celebrate we held a public event at our new offices on Hubland Nord campus, with the goal of challenging the often-negative perception of moths as boring or pests, and instead showcase their diversity, brilliant colouration, and amazing adaptations. In fact, much of our understanding of evolution comes from moths and their evolutionary arms races with their predators. We were lucky to be joined by many interested people of all walks of life, and even a film crew from the local news!

Link: https://www.br.de/br-fernsehen/sendungen/abendschau/as-motte-100.html

Moths are insects in the Order Lepidoptera (meaning scale-wing, referring to the scales on their wings that can adapt into so many designs), which is the second most diverse insect group on Earth (after beetles). As the majority of Lepidoptera are moths (the other much smaller group in this Order being butterflies), moths therefore represent a large proportion of global and local biodiversity. For example, there are around 3,000 species of Lepidoptera in Germany, with around 2,800 of those being moths. Despite this, we know very little about these nocturnal visitors, we are only just starting to understand the roles they play in their ecosystems. Recent data has shown that moths are visiting flowers at night, and are in fact more efficient at pollinating flowers than day-time pollinators such as bees! Unfortunately, data from around the world is showing large-scale and long-term declines in moth numbers, the cause of which is still under investigation, but is likely caused by a combination of land-use change (such as loss of habitat), climate change (disrupting their life cycles), and pollution (including light pollution).

We were lucky enough to be provided with a moth trap by a local moth trapping group, led by passionate students of the university who monitor the moths on campus, to demonstrate how amateur and professional entomologists survey for moths. This trap worked by hanging a UV bulb about a metre above the ground, with a net over it, so that the moths would be drawn to the light and settle on the net calmly so we could observe them. We set it up in the hopes that we would be able to find some interesting species, but sadly a storm arrived, and we had to run for shelter. Despite this, a few interesting moths did come to our light after a little while, such as Synaphe punctalis with its unusual long spiney legs, and Idaea ochrata, with many delicate markings. We also attracted several other insects, as not only moths are attracted to light, including flies, grasshoppers, and even a large carrion-eating beetle, which we were all surprised to see!

We were also kindly loaned some pinned moth specimens from the university collection, which included species such as Acherontia atropos, Saturnia pavonia, and Phalera bucephala. Many of the moths on show had stories to tell. For example, there were several Biston betularia specimens of various colours. This is a species famous for its adaptation to a world changed by human actions, where melanic (dark) forms became much more common as coal-powered industry rapidly increased and trees were covered in soot. The usually rare dark moths had an advantage over their pale relatives, who were more easily seen by predators and eaten, and so started to become very common. As time moved on and society moved away from coal power. the air was cleaned, and the tables turned on the melanic forms, which once again became rare.

With nearly 3,000 species of moths in Germany, we could only showcase a tiny fraction of this diverse group of important insects. Moths are declining around the world, and we need to act fast to preserve species before they are lost. A good place to start is by opening our eyes to the species around us, learning to appreciate them, because only through knowledge and understanding can we hope to inspire the broad-scale change needed to slow, halt, and even reverse biodiversity loss.